Notes - Learning, Motivation and Emotion

Category : Teaching

Learning, Motivation and Emotion

How do children learn?

Plato: "Children are born with knowledge that simply awaits activation".

John Locke: was of the view that the main objective of education is self-control. Children will learn properly and with interest only when the find the instruction enjoyable. Adults should use positive reinforcement such as praise rather than punishment to enable a child to learn.

Jean Jacques Rousseau: Development occurs according in a series of stages. Children should not be compelled to learn things they may not be ready for. They will learn when they are curious and it is our responsibility as adults to let the learning unfold naturally. He wrote books about a hypothetical child, Emile, where he allowed nature to raise the child so that the child is unencumbered by the pressures of the civilized society. The only way to interfere is to present lessons that were suited to the child's age and with minimal guidance and never correct Emile's mistakes.

Friedrich Froebel: saw young children as individuals who need a certain degree of freedom but also need to participate in and give society something good in return. He opened experimental preschools in Germany that he called "kindergartens" illustrating his idea that the child will grow well if properly nurtured and cared for. Froebel is best known for his emphasis on guided play as a method for learning.

John Dewey: Dewey's ideas are much like Froebel's in terms of child-centered education based on children's interests and that they learn best through play and real life experiences. School life should grow out of home life and experience. Teachers should know their children well and accordingly plan and document a purposeful curriculum. The major tenet for Dewey was problem solving that is learning through doing'.

Erik Erikson: His theory comprised of eight stages where each stage (birth to old age) has a particular issue to be resolved or accomplished before moving satisfactorily to the next stage. The stages are:

Jean Piaget: Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget showed that intelligence is the result of a natural sequence of stages and it develops as a result of the changing interaction of a child and its environment. He devised a model describing how humans go about making sense of their ' by gathering and organizing information.

Stages of development all children go through:

Cognitive development is much more than the addition of new facts and ideas to an existing store of information. According to Piaget, our thinking processes change radically, though slowly from birth to maturity because we constantly strive to make sense of the world. Piaget identifies four factors namely biological maturation, activity, social experiences, and equilibration that interact to influence thinking.

Lev Vygotsky: is of the view that social learning is inseparable from cognitive learning; they work together & build on each other. Much learning takes place in play.

Children learn cultural norms both from each other and from their parents. Vygotsky studied how speech, memory aids, writing and symbols transform the child's mind. His theory of the zone of proximal development is the distance between the most difficult task a child can do alone and the most difficult task a child can do with help. The child on the verge of learning a new concept can benefit from the interaction with a teacher or another child or his parents; this help is now referred to as scaffolding. Teachers need to plan activities carefully to challenge the children's next level. Talking is important to clarify ideas so teacher's need to encourage conversations and provide opportunities for collaborative work. Private talk is also important to thinking.

Howard Gardner:

He maintains that people have not just one but at least seven or eight separate kinds of intelligence:

Every normal person has all of these but may be high in some, and low in others and these intelligences develop at different rates.

Why children fail to achieve success in school performance?

Fear and failure: Some schools promote an atmosphere of fear and insecurity. This could be the fear of failure, humiliation, disapproval etc. that most severely affects a student's ability to grow intellectually. Extrinsic motivation such as rewards and grades and stars reinforce children's fear of failing in exams and receiving disapproval from people around them. Instead of learning the actual content of the lessons, students learn how to avoid embarrassment. This atmosphere of fear not only kills a child's love of learning and suppresses his curiosity, but also makes him afraid of taking risks which may be necessary for real learning to happen.

Boredom: Boredom serves as another big hindrance, stifling both the child's inborn motivation to learn and his love of learning. Before joining school, children feel free to explore and discover those things that interest them. But once the child becomes part of our modem school system, both the institutions and the parents unknowingly sabotage their child's education. Schools demand that children perform dull, repetitive tasks which do not give an outlet to their wide range of capabilities.

Schools focus on extrinsic rewards: These compel children to crave for petty rewards, recognition and praises rather than cultivate their intrinsic love of learning. Holt advocates that children be encouraged to learn by following their natural curiosities and interests, without fear and guilt. Extrinsic rewards take the child's attention away from intrinsic ones. The child may never understand the real reasons for doing something and may never appreciate the inherent rewards that a task will provide. For example, a child who reads a book in order to receive a sticker from the teacher may miss the point that reading has its own charm and enjoyment.

Lack of positive reinforcement: This is yet another practice prevalent in some schools. Positive reinforcement is used sparingly by some teachers. But the correct use of positive reinforcement in the classroom will work wonders in managing behavior in classrooms. Skinner advocated for immediate praise, feedback, and/or reward when seeking to change a troublesome child or encourage correct behavior in the classroom.

Strategies: Current teaching strategies increase the fear of humiliation in children, and do more to harm young people than they do to meet their needs. Such fear drives students to adopt various defense mechanisms - mumbling, acting like they don't understand, acting overly enthusiastic so they won't be called upon, etc to evade the demands placed upon them by adults or to avoid being humiliated in front of their peers.

Learning as Behaviours Change

Behaviour psychology, also known as behavioursism is a theory of learning based upon the idea that all behaviour are acquired through different methods of conditioning. Learning from a behavioursal perspective involves examining the relationship between what animals or humans do and what the environment does. When there is a change in one's behaviours in relation to environmental stimuli, behavioursists refer to such learning in terms of a conditioning process.

There are two types of conditioning based on different learning principles.

Classical Conditioning

Based on the work of Ivan Pavlov, the basis for this model lies in the range of relatively permanent and unlearned reflexes that nearly all members of a species possess. Examples include our automatic reactions to hot surfaces, food smells and a whole range of stimuli that may cause fear, anxiety, flight, or a sense of well-being. These automatic reflexes are composed of two elements: an unconditional stimulus and an unconditional response.

Again, no learning is required for these responses to take place. Where the learning, or conditioning, comes in is when another neutral stimulus is introduced in just the right way when these automatic reflexes are occurring. The classic experiments from Pavlov's laboratory involved his work with the digestive process in dogs. As the story goes, Pavlov noticed that not only would dogs salivate in the presence of food (this is the unconditional stimulus-unconditional response reflex), they also would initiate the salivary secretions even before the food arrived. This curious phenomenon set Pavlov on a course of experiments in which he discovered that various neutral stimuli, such as the sound of the attendant carrying the food or the sight of the food bowl, were enough to induce the dogs to salivate. This learning process simply required that the neutral stimuli occur in some close relationship with the food itself. Essentially then, the events just prior to actual feeding became conditional stimuli causing the conditional response of salivary secretions.

Consider, for example, a child who responds happily whenever meeting a new person who is warm and friendly, but who also responds cautiously or at least neutrally in any new situation. Suppose further that the "new, friendly person" in question is you, his teacher. Initially the child's response to you is like an unconditioned stimulus: you smile (the unconditioned stimulus) and in response he perks up, breathes easier, and smiles (the unconditioned response). This exchangeis not the whole story, however, but merely the setting for an important bit of behaviours change: suppose you smile at him while standing in your classroom, a "new situation" and therefore one to which he normally responds cautiously. Now respondent learning can occur. The initially neutral stimulus (your classroom) becomes associated repeatedly with the original unconditioned stimulus (your smile) and the child's unconditioned response (his smile). Eventually, if all goes well, the classroom becomes a conditioned stimulus in its own right: it can elicit the child's smilesand other "happy behaviour" even without your immediate presence or stimulus.

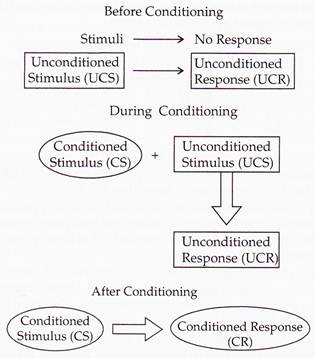

Classical conditioning occurs when a conditioned stimulus is paired with an unconditioned stimulus. Stimulus is a physical event capable of affecting behaviours. Usually, the conditioned stimulus (CS) is a neutral stimulus (e.g., the sound of a tuning fork), the unconditioned stimulus (US) is biologically potent (e.g., the taste of food) and the unconditioned response (UR) to the unconditioned stimulus is an unlearned reflex response (e.g., salivation). After pairing is repeated the organism exhibits a conditioned response (CR) to the conditioned stimulus when the conditioned stimulus is presented alone. The conditioned response is usually similar to the unconditioned response, but unlike the unconditioned response, it must be acquired through experience and is relatively impermanent.

A chart of events in classical conditioning

During his research on the physiology of digestion in dogs, Pavlov developed a procedure that enabled him to study the digestive processes of animals over long periods of time. He redirected the animal's digestive fluids outside the body, where they could be measured. Pavlov noticed that the dogs in the experiment began to salivate in the presence of the technician who normally fed them, rather than simply salivating in the presence of food. Pavlov called the dogs' anticipatory salivation, psychic secretion,

Phenomena Observed in Classical Conditioning

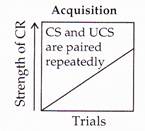

Acquisition: In classical conditioning acquisition is a gradual process in which a conditioned stimulus gradually acquires the capacity to elicit a conditioned response as a result of repeated pairing with an unconditioned stimulus.

The speed of conditioning depends on a number of factors, such as the nature and strength of both the CS and the US, previous experience and the one's motivational state. Acquisition may occur with a single pairing of the CS and US, but usually, there is a gradual increase in the conditioned response to the CS. This slows down the process as it nears completion.

Extinction: In the extinction procedure, the conditioned stimulus (CS) gradually loses the ability to elicit CR when it is no longer followed by the unconditioned stimulus (US). When this is done the CR frequency eventually returns to pre-training levels.

Reacquisition or Reconditioning: If the CS is again paired with the US, a CR is again acquired, but this second acquisition usually happens much faster than the first one.

Spontaneous Recovery; Spontaneous recovery is defined as the reappearance of the conditioned response after a time interval. That is, if the CS is tested at a later time (for example an hour or day) after conditioning it will again elicit a CR. This renewed CR is usually much weaker than the CR observed prior to extinction.

Stimulus Generalization: Stimulus generalization is said to occur if, after particular CS has come to elicit a CR, another similar stimulus will elicit the same CR. Usually the more similar are the CS and the test stimulus the stronger is the CR to the test stimulus. The more the test stimulus differs from the CS, the more the conditioned response will differ from that previously observed.

Stimulus Discrimination: Stimulus discrimination is a process in which one stimulus ("CS1") elicits one CR and another stimulus ("CS2") elicits either another CR or no CR at all. This can be brought about by, for example, pairing CS1 with an effective US and presenting CS2 with no US. Learning process is affected by temporal arrangement of the CS-UCS pairings. Temporal means time-related: the extent to which a conditioned stimulus precedes or follows the presentations of an unconditioned stimulus.

Forward Conditioning: Learning is fastest in forward conditioning. During forward conditioning, the onset of the CS preceds the onset of the US in order to signal the US will follow. Two common forms of forward conditioning are delay and trace conditioning.

Delay Conditioning: In delay conditioning the CS is presented and is overlapped by the presentation of the US.

Trace Conditioning: During trace conditioning the CS and US do not overlap. Instead, the CS begins and ends before the US is presented. The stimulus-free period is called the trace interval. It may also be called the conditioning interval. For example : If you sound a buzzer for 5 seconds and then, a second later, puff air into a person's eye, the person will blink. After several pairings of the buzzer and puff the person will blink at the sound of the buzzer alone. The difference between trace conditioning and delay conditioning is mat in the delayed procedure the CS and US overlap.

Simultaneous Conditioning: During simultaneous conditioning, the CS and US are presented and terminated at the same time. For example: If you ring a bell and blow a puff of air into a person's eye at the same moment, you have accomplished to coincide the CS and US.

Second-order and Higher-order Conditioning: This form of conditioning follows a two- step procedure. First a neutral stimulus ("CS1") conies to signal a US through forward conditioning. Then a second neutral stimulus ("CS2") is paired with the first (CS1) and comes to yield its own conditioned response. For example: a bell might be paired with food until the bell elicits salivation. If a light is then paired with the bell, then the light may come to elicit salivation as well. The bell is the CS1 and the food is the US. The light becomes the CS2 once it is paired with the CS1.

Backward Conditioning: Backward conditioning occurs "when a CS immediately follows a US. Unlike the usual conditioning procedure, in which the CS precedes the US, the conditioned response given to the CS tends to be inhibitory. For example, a puff of air directed at a person's eye could be followed by the sound of a buzzer.

Temporal Conditioning: In temporal conditioning a US is presented at regular intervals/ for instance every 10 minutes. Conditioning is said to have occurred when the CR tends to occur shortly before each US. This suggests that animals have a biological dock that can serve as a CS.

Little Albert Experiment (Phobias)

Ivan Pavlov showed that classical conditoning applied to animals. Did it also apply to humans? In a famous experiment Watson and Rayner (1920) showed that it did.

Little Albert was a 9-month-old infant who was tested on his reactions to various stimuli. He was shown a white rat. Albert showed no fear to the rat. He smiled and attempted to play with it. However what did startle him and cause him to be afraid was if a hammer was struck against a steel bar behind his head. The sudden loud noise would cause little Albert to burst into tears.

Classical Conditioning in the Classroom: If a student associates negative emotional experiences with school then this can obviously have bad results, such as creating a school phobia. For example, if a student is bullied at school they may learn to associate school with fear. It could also explain why some students show a particular dislike of certain subjects that continue throughout their academic career. This could happen if a student is humiliated or punished in class by a teacher.

In one procedure termed flooding a student suffering from a specific fear may be forced to confront the fear-eliciting stimulus without an avenue of escape. Cases in which fearful thoughts are too painful to deal with directly are treated by systematic desensitization. It is a progressive technique designed to replace anxiety with a relaxation response.

Operant Conditioning

The better known and broadly applied behavioursal model is connected with the pioneering work of E. L. Thomdike and B. F. Skinner. This approach to learning is based on the simple proposition that behaviours is a function of its consequences.

The earliest expression of this principle is Thomdike's Law of Effect, which observes that when any response is followed by a satisfactory state of affairs, it tends to be repeated. Similarly, when a behaviours is followed by an unsatisfactory or annoying result, it tends to reduce in frequency and strength.

Building on the Law of Effect/ Skinner and others created an elaborate set of ideas that explained how to increase behaviour of interest/ how to teach totally new behaviour, how to maintain learned behaviours, and how to reduce unwanted behaviours. All of these explanations rested on understanding the relationship between three elements of the puzzle: the behaviours of interest, the antecedent conditions in which the behaviours of interest was occurring, and the consequences following behaviours. The relationships among the three elements are sometimes referred to as the contingencies of reinforcement.

Building on the central idea that behavior is a function of its consequences, the next step is to examine four types of possible consequences and their effects. Two of these, positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement, tend to strengthen or increase behaviour because they result in a positive state of affairs for the subject.

Punishment can be used to suppress behaviours, but the most effective long-term solution to reduce unwanted behaviours is simply to deny reinforcement. This procedure is referred to as extinction. The most effective combination of these tools would be to use positive reinforcement to strengthen desired aspects of a subject's behaviours, while simultaneously using extinction to reduce less desired or competing behaviour. An important point to note is that punishment can be effective in the short run, but it is never a desirable long-term solution because of the negative side effects that can result, such as hostility and fear.

People respond predictably to particular stimulus situations (e.g., traffic signals, classrooms, restaurants) because they have been systematically reinforced for appropriate behaviours in those settings. Following such selective reinforcement, the stimulus situation itself comes to control behaviours, as when a red light shows at a traffic intersection or people politely stand in line at a ticket counter. Learning is also a matter of acquiring completely new behaviour that are not presently in existence.

Language-delayed children, for example, may be unable to make certain sounds that need to be part of their speech repertoire. If the children could correctly produce the sounds even occasionally, the strategy would be to simply reinforce the correct behaviours. However, if the sounds are never produced, the strategy is to use a shaping procedure in which the closest approximations are reinforced. Over time, with skilled use of reinforcement, the approximations become closer and closer to the target. This is the same strategy used in animal training, where the object is to teach behaviour the animal is capable of but are not part of their natural repertoire. Again, the strategy is to selectively reinforce closer and closer approximations until the target is reached. Finally, one important issue in behavioursal learning is the maintenance of behaviours at desired strength and frequency levels. This is where reinforcement schedules come into play. This is a complex area in itself, but the main idea is that constant reinforcement never produces the strongest and most extinction-resistant behaviours. Rather, once a behaviours is learned and can reliably occur in a particular stimulus environment, the reinforcement schedule needs to be adjusted so that reinforcement occurs only intermittently.

The Nature of Operant Conditioning

Antecedents as well as the following consequences: reinforcement and punishment are the core tools of operant conditioning. "Antecedent stimuli" occurs before a behavior happens. "Reinforcement" and "punishment" refer to their effect on the desired behaviours.

1. Reinforcement increases the probability of a behaviours being expressed or repeated.

2. "Punishment decreases the probability of a behaviours being expressed or repeated. Positive" and "negative" refer to the presence or absence of the stimulus.

1. Positive is the addition or presence of a stimulus.

2. Negative is the removal or absence of a stimulus (often adverse).

1. Positive Reinforcement (reinforcement): Occurs when a behaviours (response) is followed by a stimulus that is appetitive or rewarding, increasing the frequency of that behavior. In the Skinner box experiment, a stimulus such as food or a sugar solution can be delivered when the rat engages in a target behaviours, such as pressing a lever. This procedure is usually called simply reinforcement. Preferred activities can also be used to reinforce behaviours/ a principle referred to as the Premack Principle.

2. Negative Reinforcement (escape): Occurs when a behaviours (response) is followed by the termination of an aversive stimulus, thereby increasing that behaviours's frequency. In the Skinner box experiment, negative reinforcement can be a loud noise continuously sounding inside the rat's cage until it engages in the target behaviours, such as pressing a lever, upon which the loud noise is removed.

3. Positive Punishment (Punishment): is also called "Punishment by contingent stimulation. It occurs when a behaviours (response) is followed by a stimulus, such as introducing a shock or loud noise, resulting in a decrease in that behaviours. Positive punishment is sometimes a confusing term, as it denotes the "addition" of a stimulus or increase in the intensity of astimulus that is aversive (such as spanking or an electric shock). This procedure is usually called simply punishment.

4. Negative Punishment (penalty): is also called "Punishment by contingent withdrawal. It occurs when a behaviours (response) is followed by the removal of a stimulus, such as taking away a child's toy following an undesired behaviours, resulting in a decrease in that behaviours.

5. Extinction The procedure of not reinforcing a particular response is known as extinction. For example, a rat is first given food many times for lever presses. Then, in "extinction", no food is given. Typically the rat continues to press more and more slowly and eventually stops, at which time lever pressing is said to be "extinguished."

6. Escape and Avoidance In escape learning, a behaviours terminates an (aversive) stimulus. For example, shielding one's eyes from sunlight terminates the (aversive) stimulation of bright light in one's eyes. In avoidance learning, the behavior precedes and prevents an (aversive) stimulus, for example putting on sun glasses before going outdoors. Because, in avoidance, the stimulation does not occur, avoidance behavior seems to have no means of reinforcement.

7. Schedules of Reinforcement Schedules of reinforcement are rules that determine when and how reinforcements will be delivered. The rules specify either the time that reinforcement is to be made available, or the number of responses to be made, or both.

Token Economy: Token economy is a system in which targeted behaviors are reinforced with tokens (secondary reinforcers) and are later exchanged for rewards (primary reinforcers). Tokens can be in the form of fake money, buttons, poker chips, stickers, etc. While rewards can range anywhere from snacks to privileges or activities Teachers also use token economy at primary school by giving young children stickers to reward good behaviours.

Programmed Learning: In programmed learning, the material to be learned is broken up into small, easy steps. Since each step is easy, the learner makes few errors and has a sense of accomplishment. Programmed learning has three characteristics:

(1) the final complex task is broken up into small steps.

(2) reinforcement is contingent upon the performance of each step, and

(3) the learner makes responses at his or her own pace.

Programmed learning is thought to be an effective way of learning facts, rules and formulae.

PSI (Personalised System of Instruction): In the personalised system of instruction the material in the course is divided into small units, each of which must be mastered at a high level of proficiency before the next unit is attempted. For instance, students might be required to pass an examination at the end of each unit with a core of 90 percent, if they do not, they must study the material again until they can pass at this level.

Operant conditioning and students' learning:

Consider the following examples in which the operant behaviours tends to become more frequent on repeated occasions:

Social Learning Theory

The social learning theory proposed by Albert Bandura has become perhaps the most influential theory of learning and development. His theory added a social element, arguing that people can learn new information and behaviour by watching other people. Known as observational learning (or modeling)/ this type of learning can be used to explain a wide variety of behaviour.

Basic Social Learning Concepts

There are three core concepts at the heart of social learning theory:

1. The idea that people can learn through observation.

2. The idea that internal mental states are an essential part of this process.

3. The theory recognizes that just because something has been learned it does not mean that it will result in a change in behaviours.

1. People can learn through observation

Observational Learning: In his famous "Bobo doll" studies, Bandura demonstrated that children learn and imitate behaviour they have observed in other people. The children in Bandura's studies observed an adult acting violently toward a Bobo doll. When the children were later allowed to play in a room with the Bobo doll, they began to imitate the aggressive actions they had previously observed.

Bandura identified three basic models of observational learning:

1. A live model, which involves an actual individual demonstrating or acting out a behaviours.

2. A verbal instructional model, which involves descriptions and explanations of a behaviours.

3. A symbolic model, which involves real or fictional characters displaying behaviour in books, films, television programs, or online media.

2. Mental states are imperative to learning

Intrinsic Reinforcement: Bandura noted that external, environmental reinforcement was not the only factor to influence learning and behaviours. He described intrinsic reinforcement such as pride, satisfaction, and a sense of accomplishment. This emphasis on internal thoughts and cognitions helps link learning theories to cognitive developmental theories.

3. Learning does not necessarily lead to a change in behaviours

While behavioursists believed that learning led to a permanent change in behaviours, observational learning demonstrates that people can learn new information without demonstrating new behaviour.

The Modeling Process

All observed behaviour are not learned effectively. There are four factors that involve both the model and the learner and which can play an important role in successful social learning. The following steps are involved in the observational learning and modeling process:

Learning is a function of the interaction of personal and environmental factors.

Personal factors

Personal factors are the intra individual factors like motivation, interests, abilities etc. which predispose an individual towards learning.

Environmental factors on the other hand, are those contextual factors which highlight the role of the environment in learning, such as the socio-emotional, societal and cultural factors. Although the two factors represent different categories, they operate in a common system. The environmental factors provide the context within which the personal factors operate. The learner and the learning process can only be completely understood with reference to the interaction of both environmental and personal factors.

Intelligence

One of the key factors influencing our ability to learn effectively is intelligence. There are wide variations across individuals and cultures as to what actually constitutes intelligence.

Aptitude

Goals

Interest

Readiness to learn and maturation

Locus of control

Learning styles

Socio-cultural or environmental -factors influencing learning

Physical Environment of School:

Transform of Learning

Transfer of training or learning refers to the effect that knowledge or abilities acquired in one area have on problem solving or knowledge acquisition in other areas.

Holding (1991) says that "transfer of training occurs whenever the effects of prior learning influence the performance of a later activity. The degree to which trainees successfully apply in their jobs the skills gained in training situations, is considered "positive transfer of training" (Baldwin & Ford, 1980). There are three types of transfer of training:

MOTIVATION

Motivation is usually defined as an internal state that arouses, directs and maintains behaviour. Psychologists studying motivation focus on five basic factors

In a sense, motivation is an index of the eagerness of an individual to learn. Adequate motivation not only sets in motion the activities which results in learning, but also sustains and directs these. It is thus an indispensable factor in promoting learning, as it energizes and accelerates the process and evokes a very positive response from the learner. You would have observed that some students learn the same task or subject matter more efficiently than others, because they find it more rewarding and interesting. There can thus be a great deal of variation in 'what motivates', 'how much it motivates' and what the impact on the learner is. These variations may be attributed to differences in levels and types of motivation. For instance for some individuals, their needs determine what their motivation will be. For some others, the incentives available to accomplish a task become the most important consideration. For some others, the joy of engaging in a particular activity generates a motivational drive.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation: Intrinsic motivation is the natural tendency to seek out and conquer challenges as we pursue personal interests and exercise capabilities. When we are intrinsically motivated, we do not need incentives or punishments, because the activity itself is rewarding. For example, I study Biology outside school simply because I love the activity; no one makes me do it.

Extrinsic motivation: In contrast, when we do something in order to earn a grade, avoid punishment, please the teacher, or for some other reason that has very little to do with the task itself, we experience extrinsic motivation. We are not really interested in the activity for its own sake; we care only about what it will gain us. For example, I am working for the grade. I have no interest in the subject.

Behaviour approaches to motivation

According to the behaviour view, an understanding of student motivation begins with a careful analysis of the incentives and rewards present in the classroom. A reward is an attractive object or event supplied as a consequence of a particular behavior. For example/ a student is rewarded with bonus points when drawn an excellent diagram. An incentive is an object or event that encourages or discourages behavior.

If we are consistently reinforces for certain behaviors, we may develop habits or tendencies to act in certain ways. For example, if a student is repeatedly rewarded with affection, money, praise, or privileges for doing well in cricket but receives little recognition for studying, the student will probably work longer and harder on perfecting his batting rather than understanding geometry. Providing grades, stars, stickers and other reinforcements for learning-or demerits for misbehavior-is an attempt to motivate students by extrinsic means of incentives/ rewards and punishments.

Humanistic approaches to motivation

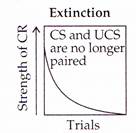

Humanistic interpretations of motivation emphasize intrinsic sources of motivation such as a person's need for self-actualization, the inborn actualizing tendency or the need for "self- determination". From the humanistic perspective, to motivate means to encourage people's inner resources- their sense of competence, self-esteem, autonomy, and self-actualization. Maslow's theory is a very influential humanistic explanation of motivation.

Maslow's Hierarchy

Abraham Maslow suggested that humans have a hierarchy of needs ranging from lower-level needs for survival and safety to higher-level needs for intellectual achievement and finally self- actualization. Self-actualization means self-fulfillment, the realization of personal potential. Each of the lower needs must be met before the next higher need can be addressed. Maslow called the four lower level needs-for survival, then safety, followed by belonging, and then self-esteem-deficiency needs. When these needs are satisfied, the motivation for fulfilling them decreases. He labeled the three higher level needs- intellectual achievement, then aesthetic appreciation, and finally self-actualization-being needs. When they are met, a person's motivation does not cease; instead it increases to seek further fulfillment. Unlike the deficiency needs, the being needs can never be completely filled. For example, the more successful you are in your efforts to develop as a teacher, the harder you are likely to strive for even greater improvement.

Cognitive approaches to motivation

Cognitive theorists believe that behavior is determined by our thinking, not simply by whether we have been rewarded or punished for the behavior in the past. These theorists emphasize intrinsic motivation.

Attribution theory

This cognitive explanation of motivation begins with the assumption that we try to make sense of our own behavior and the behavior of others by searching for explanations and causes. To understand our own successes and failures, particularly unexpected ones, we all ask "Why?" Students ask themselves, "Why did I flunk midterm?" or why did I do so well this time?" They may attribute their successes and failures to ability, effort, mood/ knowledge, luck, help, interest, clarity of instructions, the interference of others, unfair policies, and so on. To understand the success and failures of others, we also make attributions- that the others are smart or lucky or work hard.

Bernard Weiner is one of the main educational psychologists responsible for relating attribution theory to school learning. According to Weiner, most of the attributed causes for successes or failures can be characterized in terms of three dimensions:

1. Locus (location of the cause internal or external to the person)

2. Stability (whether the cause stays the same or can change) and,

3. Controllability (whether the person can control the cause)

Every cause for success or failure can be categorized on these three dimensions. For example, luck is external (locus), unstable (stability), and uncontrollable (controllability)

Attributions in the classroom

When usually successful students fail, they often make internal controllable attributions. They misunderstood the directions, lacked the necessary knowledge, or simply did not study hard enough, for example. As a consequence, they usually focus on strategies for succeeding next time. This response often leads to achievement, pride and a greater feeling of control.

Motivation to Learn in School

Teachers are concerned about developing a particular kind of motivation in their students-the motivation to learn. Student motivation to learn is defined as "a student tendency to find academic activities meaningful and worthwhile and to try to derive the intended academic benefits from them. Motivation to learn can be construed as both a general trait and a situation specific trait. Motivation to learn involves more than wanting or intending to learn. It includes the quality of the student's mental efforts. For example, reading the text 10 times may indicate persistence, but motivation to learn implies more thoughtful, active, study strategies, such as summarizing, elaborating the basic ?ideas, outlining in your own words, drawing graphs of the key relationships/ and so on.

It would be wonderful if all our students came to us filled with the motivation to learn, but they don't. And even if they did, work in school might still seem boring or unimportant to some students. As teachers, we have three major goals. The first is to get students productively involved with the work of the class; in other words, to create a state of motivation to learn. The second and longer term goal is to develop in our students the trait of being motivated to learn so they will be able "to educate themselves throughout their lifetime". And finally, we want our students to be cognitively engaged-to think deeply about what they study. In other words, we want them to be thoughtful.

THE TARGET MODAL FOR SUPPORTINGSTUDENT MOTIVATION TO LEARN

Teacher make decisions in many areas that can influence motivation to learn. The TARGET acronym highlight task, autonomy, recognition, grouping, evaluation and time.

|

Target area |

Focus |

Objectives |

Examples of possible strategies |

|

TASK |

|

|

|

|

AUTONOMY / RESPONSIBILITY |

|

|

|

|

RECOGNITION |

|

|

|

|

GROUPING |

|

|

|

|

EVALUATION |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TIME |

|

|

|

EMOTION ANP COGNITION

Emotions are complex. The main stream definition of emotion refers to a feeling state involving thoughts/physical and physiological reactions that influence our behaviour. The physiology of emotion is closely linked to arousal of the nervous system with various states and strengths of arousal relating, apparently, to particular emotions. Emotion is also linked to behaviour tendency. Extroverted people are more likely to be social and express their emotions, while introverted people are more likely to be more socially withdrawn and conceal their emotions. Emotion is often the driving force behind motivation, positive or negative. An alternative definition of emotion is a "positive or negative experience that is associated with a particular pattern of physiological activity".

Emotions involve different components, such as subjective experience, cognitive processes/ expressive behaviour, psychophysiological changes, and instrumental behaviour. At one time, academics attempted to identify the emotion with one of the components: William James with a subjective experience, behayiorists with instrumental behavior, psychophysiologists with physiological changes, and so on. More recently, emotion is said to consist of all the components.

Emotion can be differentiated from a number of similar constructs within the field of affective neuroscience:

In addition, relationships exist between emotions, such as having positive or negative influences, with direct opposites existing. These concepts are described in contrasting and categorisation of emotions. Graham differentiates emotions as functional or dysfunctional and argues all functional emotions have benefits.

Components of Emotion

In Scherer's components processing model of emotion, five crucial elements of emotion are said to exist. From the component processing perspective, emotion experience is said to require that all of these processes become coordinated and synchronized for a short period of time, driven by appraisal processes.

Theories of Emotion

James-Lange Theory: In his theory, James proposed that the perception of what he called an "exciting fact" directly led to a physiological response, known as "emotion." To account for different types of emotional experiences, James proposed that stimuli trigger activity in the autonomic nervous system, which in turn produces an emotional experience in the brain.

An example of this theory in action would be as follows: An emotion-evoking stimulus (snake) triggers a pattern of physiological response (increased heart rate, faster breathing, etc.), which is interpreted as a particular emotion (fear). This theory is supported by experiments in which by manipulating the bodily state induces a desired emotional state. Some people may believe that emotions give rise to emotion-specific actions: e.g. "I'm crying because I'm sad," or "I ran away because I was scared."

EVENT![]() AROUSAL

AROUSAL![]() INTERPRETATION

INTERPRETATION![]() EMOTION

EMOTION

Additional support for the James-Lange theory of emotion is provided by studies of the facial feedback hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that changes in our facial expression sometime produce shifts in our emotional experience rather than merely mirroring them.

Cannon-Bard Theory: Walter Bradford Cannon agreed that physiological responses played a crucial role in emotions, but did not believe that physiological responses alone could explain subjective emotional experiences.

He suggested that physiological responses were too slow and often imperceptible and this could not account for the relatively rapid and intense subjective awareness of emotion. He also believed that the richness, variety, and temporal course of emotional experiences could not stem from physiological reactions that reflected fairly undifferentiated fight or flight responses. An example of this theory in action is as follows: An emotion-evoking event (snake) triggers simultaneously both a physiological response and a conscious experience of an emotion.

![]() AROUSAL

AROUSAL

EVENT

![]() EMOTION

EMOTION

Schechter-Singer's Two-factor Theory: He suggested that physiological responses contributed to emotional experience by facilitating a focused cognitive appraisal of a given physiologically arousing event and that this appraisal was what defined the subjective emotional experience. Emotions were thus a result of two- stage process: general physiological arousal, and experience of emotion. For example, the physiological arousal, heart pounding, in a response to an evoking stimulus, the sight of snake in the kitchen. The brain then quickly scans the area, to explain the pounding, and notices the snake. Consequently, the brain interprets the pounding heart as being the result of fearing the snake

EVENT ![]() AROUSAL

AROUSAL![]() REASONING

REASONING ![]() EMOTION

EMOTION

Cognitive Theories: With the two-factor theory now incorporating cognition, several theories began to argue that cognitive activity in the form of judgments, evaluations, or thoughts were entirely that necessary for an emotion to occur. One of the main proponents of this view was Richard Lazarus who stated emotions must have some cognitive intentionality. The cognitive activity involved in the interpretation of an emotional context may be conscious or unconscious and may or may not take the form of conceptual processing.

Lazarus' theory is very influential; emotion is a disturbance that occurs in the following order:

1. Cognitive appraisal: The individual perceives the event cognitively, which cues the emotion.

2. Physiological changes: The cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response.

3. Action : The individual feels the emotion after cognition and chooses how to react

For example: Henry sees a snake.

1. Henry cognitively assesses the snake in her presence. Cognition allows her to understand it as a danger.

2. Her brain activates Adrenaline gland which pumps Adrenaline through her blood stream resulting in increased heartbeat.

3. Henry screams and runs away.

Lazarus stressed that the quality and intensity of emotions are controlled through cognitive processes.

EVENT![]() THOUGHT

THOUGHT ![]() EMOTION

EMOTION

![]() AROUSAL

AROUSAL

George Mandler provided an extensive theoretical and empirical discussion of emotion as influenced by cognition consciousness, and the autonomic nervous system.

A prominent philosophical exponent Robert C. Solomon claimed that emotions are cognitive activity in the form of judgments. He has demonstrated a more nuanced view which responds to what he has called the 'standard objection' to cognitivism, the idea that a judgement that something is fearsome can occur with or without emotion, so judgement cannot be identified with emotion. The theory proposed by Nico Frijda where appraisal leads to action tendencies is another example.

Perceptual Theory: Argues this theory that bodily responses are central to emotions, yet it emphasises the meaningfulness of emotions or the idea that emotions are about something, as is recognised by cognitive theories. The novel claim of this theory is that conceptually-based cognition is unnecessary for such meaning. Rather the bodily changes themselves perceive the meaningful content of the emotion because of being causally triggered by certain situations.

Affective Events Theory: Developed by Howard M. Weiss and Russell Cropanzano 1996 this is a communication-based theory that looks at the causes, structures, and consequences of emotional experience (especially in work contexts). This theory discovers that emotions are influenced and caused by events which in turn influence attitudes and behaviors. This theoretical frame also emphasises time in that human beings experience what they call emotion episodes? a "series of emotional states extended over time and organised around an underlying theme." This theory has been utilized by numerous researchers to better understand emotion from a communicative lens, and was reviewed further by Howard M. Weiss and Daniel J. Beal.

Emotion and Cognition

Our thoughts seem to exert strong effects on our emotions. This relationship works in the other directions as well. Being in a happy mood often causes us to think happy thoughts, while feeling sad lends to bring negative memories and images to mind. In short, there appear to be important links between the way we feel and the way we think.

How Affect Influences Cognition:

Affect/ our current mood strongly influence our perception of ambiguous stimuli. In general, we perceive and evaluate these stimuli more favorably when we are in good mood than when we are in a negative one. Positive and negative moods exert a strong influence on memory. According to Forgas information consistent with our current mood is easier to remember than information inconsistent with it. According to Isen & Daubman, persons experiencing positive effect are seen to include a wider range of information within various memory categories than do persons in a neutral or negative mood* Our current mood often influences the process of decision making. Persons experiencing positive effect are indeed more likely to make risky decisions the potential losses involved are small or very unlikely to occur. Persons in a good mood are sometimes more creative than those in negative mood. They are more successful in performing tasks involving creative problem-solving..

You need to login to perform this action.

You will be redirected in

3 sec