NCERT Extracts - Knowing Gandhi

Category : UPSC

Gandhiji

- Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October, 1869 at Porbandar in Gujarat.

- After getting his legal education in Britain, he went to South Africa to practice law.

- Imbued with a high sense of justice, he was revolted by the racial injustice, discrimination and degradation to which Indians had to submit in the South African colonies.

- Indian labourers who had gone to South Africa, and the merchants who followed were denied the right to vote. They had to resister and pay to poll-tax.

²

- They could not reside except in prescribed locations which were insanitary and congested.

- Gandhi soon became the leader of the struggle against these conditions and during 1893- 1914 was engaged in a heroic though unequal struggle against the racist authorities of South Africa.

- It was during this long struggle lasting nearly two decades that he evolved the technique of satyagraha based on truth and non-violence.

- In January, 1915, Gandhiji returned to his homeland at the age of 46.

- As the historian Chandran Devanesan has remarked, South Africa was "the making of the Mahatma".

- Gandhiji's acknowledged political mentor was Gopal Krishna Gokhale.

- On Gokhale's advice, Gandhiji spent a year travelling around British India, getting to know the land and its peoples.

- In 1916, he founded the Sabarmati Ashram at Ahmedabad where his friends and followers were to leam and practise the ideas of truth and non-violence.

- His first major public appearance was at the opening of the Banaras Hindu University (BHU) in February, 1916.

- When his turn came to speak, Gandhiji charged the Indian elite with a lack of concern for the labouring poor. The opening of the BHU, he said, was "certainly a most gorgeous show". But he worried about the contrast between the "richly bedecked noblemen" present and "millions of the poof Indians who were absent.

- Gandhiji told the privileged invitees that "there is no salvation for India unless you strip yourself of this jewellery and hold it in trust for your countrymen in India". "There can be no spirit of self-government about us," he went on, "if we take away or allow others to take away from the peasants almost the whole of the results of their labour. Our salvation can only come through the farmer. Neither the lawyers, nor the doctors, nor the rich landlords are going to secure it."

- Gandhiji's speech at Banaras in February, 1916 was, at one level, merely a statement of fact - namely, that Indian nationalism was an elite phenomenon, a creation of lawyers and doctors and landlords.

- But, at another level, it was also a statement of intent - the first public announcement of Gandhiji's own desire to make Indian nationalism more properly representative of the Indian people as a whole.

- In the last month of that year, Gandhiji was presented with an opportunity to put his precepts into practice.

- At the annual Congress, held in Lucknow in December, 1916, he was approached by a peasant from Champaran in Bihar, who told him about the harsh treatment of peasants by British indigo planters.

Champaran Satyagraha (1917)

- Gandhi's first great experiment in satyagraha came in 1917 in Champaran, a district in Bihar.

- The peasantry on the indigo plantations in the district was excessively oppressed by the European planters.

- They were compelled to grow indigo on at least 3/20th of their land and to sell it at prices fixed by the planters.

- Accompanied by Babu Rajendra Prasad, Mazhar-ul-Huq, J.B. Kripalani, Narhari Parekh and Mahadev Desai, Gandhiji reached Champaran in 1917 and began to conduct a detailed inquiry into the condition of the peasantry.

- The infuriated district official ordered him to leave Champaran, but he defied the order and was willing to face trial and imprisonment.

- This forced the government to cancel its earlier order and to appoint a committee of inquiry on which Gandhiji served as a member.

- Ultimately, the disabilities from which the peasantry was suffering were reduced and Gandhiji had won his first battle of civil disobedience in India.

- He had also had a glimpse into the naked poverty in which the peasants of India lived.

Ahmedabad Mill Strike

- In 1918, Mahatma Gandhi intervend in a dispute between the workers and mill owners of Ahmedabad. He advised the workers to go on strike and to demand a 35 per cent increase in wages. But he insisted that the workers should not use violence against the employers during the strike.

- He undertook a fast unto death to strengthen the workers resolve to continue the strike. But his fast also put pressure on the mill-owners who relented on the fourth day and agreed to give the workers a 35 per cent increase in wages.

Kheda Peasant Struggle

- In 1918, crops failed in the Kheda District in Gujarat but the government refused to remit land revenue and insisted on its full collection.

- Gandhiji supported withhold payment of revenue till their demand for its remission was met. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was one of the many young persons who became GandhyTs followers during the Kheda peasant struggle.

- These experiences brought Gandhiji in close contact with the masses whose interests he actively espoused all his life.

- These initiatives in Champaran, Ahmedabad and Kheda marked Gandhiji out as a nationalist with a deep sympathy for the poor.

Rowlatt Satyagraha

- Then, in 1919, the colonial rulers delivered into Gandhiji's lap an issue from which he could construct a much wider movement. Gandhiji called for a countrywide campaign against the "Rowlatt Act". Gandhiji was detained while proceeding to the Punjab.

- It was the Rowlatt satyagraha that made Gandhiji a truly national leader. Emboldened by its success, Gandhiji called for a campaign of "non-cooperation" with British rule.

- If noncooperation was effectively carried out, said Gandhiji, India would win swaraj within a year. To further broaden the struggle he had joined hands with the Khilafat Movement.

Non-Cooperation (1920-22)

- Non-Cooperation Movement was started by Ghanhiji on 1st August, 1920.

- Gandhiji hoped that by coupling non-cooperation with Khilafat, India's two major religious communities, Hindus and Muslims, could collectively bring an end to colonial rule.

- "Non-cooperation," wrote Mahatma Gandhi's American biographer Louis Fischer, "became the name of an epoch in the life of India and of Gandhiji. It entailed denial, renunciation, and self-discipline. It was training for self-rule."

- Then, in February, 1922, a group of peasants attacked and torched a police station in the hamlet of Chauri Chaura.

- This act of violence prompted Gandhiji to call off the movement altogether.

- "No provocation," he insisted, "can possibly justify (the) brutal murder of men who had been rendered defenceless and who had virtually thrown themselves on the mercy of the mob."

- During the Non-Cooperation Movement thousands of Indians were put in jail. Gandhiji himself was arrested in March, 1922, and charged with sedition.

- The judge who presided over his trial. Justice C.N. Broomfield, made a remarkable speech while pronouncing his sentence. "It would be impossible to ignore the fact," remarked the judge, "that you are in a different category from any person I have ever tried or am likely to try. It would be impossible to ignore the fact that, in the eyes of millions if your countrymen, you are a great patriot and a leader. Even those who differ from you in politics look upon you as a man of high ideals and of even saintly life.”

- Since Gandhiji had violated the law it was obligatory for the Bench to sentence him to six years5 imprisonment, but, said Judge Broomfield, "If the course of events in India should make it possible for the Government to reduce the period and release you, no one will be better pleased than I".

A Peopled Leader

- By 1922, Gandhiji had transformed Indian nationalism, thereby redeeming the promise he made in his BHU speech of February, 1916.

- It was no longer a movement of professionals and intellectuals; now, hundreds of thousands of peasants, workers and artisans also participated in it.

- Many of them venerated Gandhiji, referring to him as their Mahatma.

- They appreciated the fact that he dressed like them, lived like them, and spoke their language. Unlike other leaders he did not stand apart from the common folk, but empathized and even identified with them.

- This identification was strikingly reflected in his dress: while other nationalist leaders dressed formally, wearing a Western suit or an Indian bandgala, Gandhiji went among the people in a simple dhoti or loincloth.

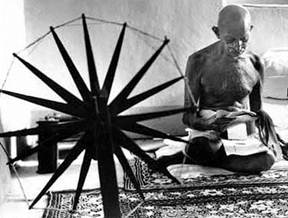

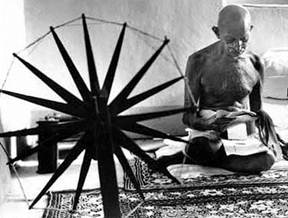

- Meanwhile, he spent part of each day working on the charkha (spinning wheel), and encouraged other nationalists to do likewise.

- The act of spinning allowed Gandhiji to break the boundaries that prevailed within the traditional caste system, between mental labour and manual labour.

- In a fascinating study, the historian Shahid Amin has traced the image of Mahatma Gandhi among the peasants of eastern Uttar Pradesh, as conveyed by reports and rumours in the local press.

- When he travelled through the region in February, 1921, Gandhiji was received by adoring crowds everywhere. This is how a Hindi newspaper in Gorakhpur reported the atmosphere during his speeches.

- Wherever Gandhiji went, rumours spread of his miraculous powers. In some places it was said that he had been sent by the King to redress the grievances of the farmers, and that he had the power to overrule all local officials.

- In other places it was claimed that Gandhiji's power was superior to that of the English monarch, and that with his arrival the colonial rulers would flee the district.

- There were also stories reporting dire consequences for those who opposed him; rumours spread of how villagers who criticised Gandhiji found their houses mysteriously falling apart or their crops failing.

- Known variously as "Gandhi baba", "Gandhi Maharaj", or simply as "Mahatma", Gandhiji appeared to the Indian peasant as a saviour, who would rescue them from high taxes and oppressive officials and restore dignity and autonomy to their lives.

- Mahatma Gandhi was by caste a merchant, and by profession a lawyer; but his simple lifestyle and love of working with his hands allowed him to empathise more fully with the labouring poor and for them, in turn, to empathise with him.

- Where most other politicians talked down to them, Gandhiji appeared not just to look like them, but to understand them and relate to their lives.

- Gandhiji encouraged the communication of the nationalist message in the mother tongue, rather than in the language of the rulers, English.

- While Mahatma Gandhi's own role was vital, the growth of what we might call "Gandhian nationalism" also depended to a very substantial extent on his followers.

- Between 1917 and 1922, a group of highly talented Indians attached themselves to Gandhiji.

- They included Mahadev Desai, Vallabh Bhai Patel, J.B. Kripalani, Subhas Chandra Bose, Abul Kalam Azad, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu, Govind Ballabh Pant and C. Rajagopalachari.

- Notably, these close associates of Gandhiji came from different regions as well as different religious traditions. In turn, they inspired countless other Indians to join the Congress and work for it.

- Mahatma Gandhi was released from prison in February, 1924, and now chose to devote his attention to the promotion of home-spun cloth (khadi), and the abolition of untouchability.

- He believed that in order to be worthy of freedom, Indians had to get rid of social evils such as child marriage and untouchability.

- Indians of one faith had also to cultivate a genuine tolerance for Indians of another - hence his emphasis on Hindu-Muslim harmony.

- Meanwhile, on the economic front Indians had to leam to become self-reliant – hence his stress on the significance of wearing khadi rather than mill-made cloth imported from overseas.

- For several years after the Non-cooperation Movement ended, Mahatma Gandhi focused on his social reform work. In 1928, however, he began to think of re-entering politics.

- In 1928, there was an all-India campaign in opposition to the all-White Simon Commission, sent from England to enquire into conditions in the colony.

- Gandhiji did not himself participate in this movement, although he gave it his blessings, as he also did to a peasant satyagraha in Bardoli in the same year.

- On 26 January, 1930, "Independence Day" was observed, with the national flag being hoisted in different venues, and patriotic songs being sung. Gandhiji himself issued precise instructions as to how the day should be observed.

- "It would be good," he said, "if the declaration [of Independence] is made by whole villages, whole cities even ... It would be well if all the meetings were held at the identical minute in all the places."

- Gandhiji suggested that the time of the meeting be advertised in the traditional way, by the beating of drums. The celebrations would begin with the hoisting of the national flag.

- The rest of the day would be spent "in doing some constructive work, whether it is spinning, or service of 'untouchables9, or reunion of Hindus and Mussalmans, or prohibition work, or even all these together, which is not impossible".

Dandi

- Soon after the observance of this "Independence Day", Mahatma Gandhi announced that he would lead a march to break one of the most widely disliked laws in British India, which gave the state a monopoly in the manufacture and sale of salt.

- His picking on the salt monopoly was another illustration of Gandhiji's tactical wisdom.

- For in every Indian household, salt was indispensable; yet people were forbidden from making salt even for domestic use, compelling them to buy it from shops at a high price.

- The state monopoly over salt was deeply unpopular; by making it his target, Gandhiji hoped to mobilise a wider discontent against British rule.

- Where most Indians understood the significance of Gandhiji's challenge, the British Raj apparently did not. Although Gandhiji had given advance notice of his "Salt March” to the Viceroy Lord Irwin, Irwin failed to grasp the significance of the action.

- On 12 March, 1930, Gandhiji began walking from his ashram at Sabarmati towards the ocean. He reached his destination three weeks later, making a fistful of salt as he did and thereby making himself a criminal in the eyes of the law.

- The progress of Gandhiji's march to the seashore can be traced from the secret reports filed by the police officials deputed to monitor his movements.

- In one village, Wasna, Gandhiji told the upper castes that "if you are out for Swaraj you must serve untouchables. You won't get Swaraj merely by the repeal of the salt taxes or other taxes. For Swaraj you must make amends for the wrongs which you did to the untouchables. For Swaraj, Hindus, Muslims, Parsis and Sikhs will have to unite. These are the steps towards Swaraj."

- The progress of the Salt March can also be traced from another source: the American newsmagazine. Time. This, to begin with, scorned at Gandhiji's looks, writing with disdain of his "spindly frame" and his "spidery loins".

- Thus in its first report on the march. Time was deeply sceptical of the Salt March reaching its destination. It claimed that Gandhiji "sank to the ground" at the end of the second day's walking; the magazine did not believe that "the emaciated saint would be physically able to go much further".

- But within a week it had changed its mind. The massive popular following that the march had garnered, wrote Time, had made the British rulers "desperately anxious".

- Gandhiji himself they now saluted as a "Saint" and "Statesman", who was using "Christian acts as a weapon against men with Christian beliefs".

Why the Salt Satyagraha?

- Why was salt the symbol of protest? This is what Mahatma Gandhi wrote: The volume of information being gained daily shows how wickedly the salt tax has been designed. In order to prevent the use of salt that has not paid the tax which is at times even fourteen times its value, the Government destroys the salt it cannot sell profitably.

- Thus it taxes the nation's vital necessity; it prevents the public from manufacturing it and destroys what nature manufactures without effort. No adjective is strong enough for characterising this wicked dog-in-the-manger policy.

- From various sources I hear tales of such wanton destruction of the nation's property in all parts of India. Mounds if not tons of salt are said to be destroyed on the Konkan coast.

- Thus valuable national property is destroyed at national expense and salt taken out of the mouths of the people.

- "Tomorrow we shall break the salt tax law”

- Even while I was at Sabarmati there was a rumour that I might be arrested. I had thought that the Government might perhaps let my party come as far as Dandi, but not me certainly.

- If someone says that this betrays imperfect faith on my part, I shall not deny the charge. That I have reached here is in no small measure due to the power of peace and non-violence: that power is universally felt.

- The Government may, if it wishes, congratulate itself on acting as it has done, for it could have arrested every one of us. In saying that it did not have the courage to arrest this army of peace, we praise it. It felt ashamed to arrest such an army,

- He is a civilised man who feels ashamed to do anything which his neighbours would disapprove. The Government deserves to be congratulated on not arresting us, even if it desisted only from fear of world opinion.

- Tomorrow we shall break the salt tax law. Whether the Government will tolerate that is a different question. It may not tolerate it, but it deserves congratulations on the patience and forbearance it has displayed in regard to this party. ...

- What if I and all the eminent leaders in Gujarat and in the rest of the country are arrested? This movement is based on the faith that when a whole nation is roused and on the march no leader is necessary.

Dialogues

- The Salt March was notable for at least three reasons.

- First, it was this event that first brought Mahatma Gandhi to world attention. The march was widely covered by the European and American press.

- Second, it was the first nationalist activity in which women participated in large numbers.

- Third, and perhaps most significant, it was the Salt March which forced upon the British the realisation that their Raj would not last forever, and that they would have to devolve some power to the Indians.

- To that end, the British government convened a series of “Reiiad Table CoirfereEiees” m London. Gandhiji was released from jail in January, 1931 and the following month had several long meetings with the Viceroy. These culminated in what was called the “Gandhi-Irwin Pact".

- A second Round Table Conference was held in London in the latter part of 1931. Here, Gandhiji represented the Congress.

- The Conference in London was inconclusive, so Gandhiji returned to India and resumed civil disobedience.

- The new Victory, Lord Willingdon, was deeply unsympathetic to the Indian leader.

- In the spring of “1942, Churchill was persuaded to send one of his minister, Sir Stafford Cripps, to India to try and forge a compromise with Gandhiji and the Congress.

- After the failure of the Cripps Mission, Mahatma Gandhi decided to launch his third major movement against British rule. This was the "Quit India" campaign, which began in August, 1942. Although Gandhiji was jailed at once, younger activists organized strikes and acts of sabotage all over the country.

- "Quit India" was genuinely a mass movement, bringing into its ambit hundreds of thousands of ordinary Indians.

- In June, 1944 Gandhiji was released from prison. Later that year he held a series of meetings with Jinnah, seeking to bridge the gap between the Congress and the League.

- In February, 1947, Wavell was replaced as Viceroy by Lord Mountbatten.

- The formal transfer of power was fixed for 15 August.

The Last Heroic Days

- As it happened, Mahatma Gandhi was not present at the festivities in the capital on 15 August, 1947. He was in Calcutta, but he did not attend any function or hoist a flag there either. Gandhiji marked the day with a 24-hour fast.

- Through September and October, writes his biographer D.G. Tendulkar, Gandhiji "went round hospitals and refugee camps giving consolation to distressed people". He "appealed to the Sikhs, the Hindus and the Muslims to forget the past and not to dwell on their sufferings but to extend the right hand of fellowship to each other, and to determine to live in peace ..."

- At the initiative of Gandhiji and Nehru, the Congress now passed a resolution on "the rights of minorities". The party had never accepted the "two-nation theory".

- Many scholars have written of the months after Independence as being Gandhiji's "finest hour". After working to bring peace to Bengal, Gandhiji now shifted to Delhi, from where he hoped to move on to the riot-torn districts of Punjab.

- While in the capital, his meetings were disrupted by refugees who objected to readings from the Koran, or shouted slogans asking why he did not speak of the sufferings of those Hindus and Sikhs still living in Pakistan.

- In fact, as D.G. Tendulkar writes, Gandhiji "was equally concerned with the sufferings of the minority community in Pakistan. He would have liked to be able to go to their succour. But with what face could he now go there, when he could not guarantee full redress to the Muslims in Delhi?"

- However, he trusted that "the worst is over", that Indians would henceforth work collectively for the "equality of all classes and creeds, never the domination and superiority of the major community over a minor, however insignificant it may be in numbers or influence".

- He also permitted himself the hope "that though geographically and politically India is divided into two, at heart we shall ever be friends and brothers helping and respecting one another and be one for the outside world”. Was divided, he urged that the two parts respect and befriend one another.

- Other Indians were less forgiving. At his daily prayer meeting on the evening of 30 January, 1948, Gandhiji was shot dead by a young man.

- The assassin, who surrendered afterwards, was a Brahmin from Pune named Nathuram Godse, the editor of an extremist Hindu newspaper who had denounced Gandhiji as "an appeaser of Muslims".

- Gandhiji's death led to an extraordinary outpouring of grief, with rich tributes being paid to him from across the political spectrum in India, and moving appreciations coming from such international figures as George Orwell and Albert Einstein.

- Time magazine, which had once mocked Gandhiji's physical size and seemingly non- rational ideas, now compared his martyrdom to that of Abraham Lincoln.

Truth and Non-Violence

- According to Gandhi, an ideal satyagrahi was to be truthful and perfectly peaceful, but at the same time he would refuse to submit to what he considered wrong.

- He would accept suffering willingly in the course of struggle against the wrong-doer.

- This struggle was to be part of his love of truth. But even while resisting evil, he would love the evil-doer.

- Hatred would be alien to the nature of a true satyagrahi. He would, moreover, be utterly fearless. He would never bow down before evil whatever the consequences.

- In Gandhi's eyes, non-violence was not a weapon of the weak and cowardly.

- Only the strong and the brave could practise it. Even violence was preferable to cowardice.

- In a famous article in his weekly journal, Young India, he wrote in 1920 that, “Non- violence is the law of our species, as violence is the law of the brute”. But that "where there is only a choice between cowardice and iolence, I would advise violence. I would rather have India resort to arms in order to defend her honour, than that she should, in a cowardly manner, become or remain a helpless witness to her own dishonour".

- He once summed up his entire philosophy of life as follows: "The only virtue I want to claim is truth and non-violence. I lay no claim to super-human powers, I want none".

- Another important aspect of Gandhi's outlook was that he would not separate thought and practice, belief and action. His truth and non-violence were meant for daily living and not merely for high-sounding speeches and writings.

Faith in the Capacity of the Common People

- Gandhiji had an immense faith in the capacity of the common people to fight.

- For example, in 1915, at Madras, he said: "You have said that I inspired these great men and women, but I cannot accept that proposition. It was they, the simple- minded folk, who worked away in faith, never expecting the slightest reward, who inspired me, who kept me to the proper level, and who compelled me.

- Similarly in 1942, when asked how he expected “to resist the might of the Empire”. He replied: “with the might of the dumb millions.

- Three other causes were very dear to Gandhi's heart. The first was Hindu-Muslim unity, the second, the fight against untouchability, and the third, the raising of the social status of women in the country.

- He once summed up his aims as follows: "I shail work for an India in which the poorest shall feel that it is their country. An India in which all communities shall live in perfect harmony. This is the India of my dreams”.

- Though a devout Hindu, Gandhi "s cultural and religious outlook was universalist and not narrow.

- He said: "I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any. I refuse to live in other people’s houses as an interloper, a beggar or a slaved

Charkha

- Mahatma Gandhi was profoundly critical of the modem age in which machines enslaved humans and displaced labour. He saw the charkha as a symbol of a human society that would not glorify machines and technology. The spinning wheel, moreover, could provide the poor with supplementary income and make them self-reliant.

- What I object to, is the craze for machinery as such. The craze is for what they call laboursaving machinery. Men go on “saving labour”, till thousands are without work and thrown on the open streets to die of starvation. I want to save time and labour, not for a fraction of mankind, but for all; I want the concentration of wealth, not in the hands of few, but in the hands of all.

- Khaddar does not seek to destroy all machinery but it does regulate its use and check its weedy growth. It uses machinery for the service of the poorest in their own cottages. The wheel is itself an exquisite piece of machinery.

Some Important fact

²

- Mahatma Gandhi regularly published in his journal, Harijan, letters that others wrote to him. Nehru edited a collection of letters written to him during the national movement and published A Bunch of Old Letters.