Category : 8th Class

Marginalisation and Social Justice

The sides or fringes of something are its margins. So, moving away or being made to move away from the centre of an activity or a group is called being marginalised. A newcomer in a school or neighbourhood may feel marginalised, a child with a learning disability may feel marginalised in class, and a foreign student in an Indian university may feel marginalised. As you may have guessed from these examples, some elements of being marginalised are being dismcluded, being ridiculed and bullied, and feeling powerless.

MEANING OF MARGINALISATION

Marginalised communities or groups are not included in the process of decision-making and are deprived of the benefits of development. These groups are often minorities, or small groups that are different from the majority in religion, race or language. However, all minority communities need not be marginalised. In India, for example, Christians, Sikhs and Jains are minorities, but they are not marginalised. On the other hand, the dominant (powerful) community need not always be in majority. Until 1994, Whites formed the dominant community in South Africa, though Coloured people were in majority. Remember that the term 'minority' is used in the context of numbers, while the term 'marginalised' is used in the context of social, political and economic status, or position.

Marginalised communities face social disinclusion, mistrust, ridicule and hostility. This often drives them to live together in small areas or pockets of a town/city. Such urban areas, inhabited mostly by members of the same (usually minority) community, are called ghettos. For example, Harlem, in New York, is an area inhabited mostly by African-Americans. The process which leads to the formation of ghettos is called ghettoisation.

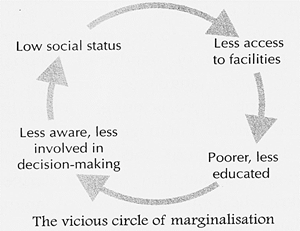

The low social status of marginalised communities usually translates into low economic status. They are less educated, have less access to facilities such as schools, hospitals, housing, piped water and electric supply. Being less educated, they are less aware of their rights, and having a low economic and social status, they are less able to fight for their rights. Their participation in the planning and decision-making processes of society is less significant. This makes it difficult for them to break the vicious circle of marginalisation and become a part of the mainstream. A vicious circle is a sequence of cause and effect that are interconnected, and by the term 'mainstream' we mean the influential or generally accepted group/groups in society.

MARGINALISED GROUPS IN INDIA

The Constitution forbids discrimination on the basis of race, religion/ language, sex, and so on. However, in reality certain communities are still looked upon as the 'others' by a large part (if not by a majority) of the population. Even law-makers, government officials, the police and judges sometimes have these biases, so these communities find it difficult to seek justice. Women, the elderly (old people) and the disabled also face discrimination in India.

THE ADIVASIS

The term Adivasi is used to refer to the tribal people of India. According to the 2011 Census, they constitute about 8.6% of our population. They are believed to be the most ancient inhabitants of our land. Hence, the name Adivasi. At the end of the main text of the Constitution, there is a schedule (list) of the various tribal groups in our country. Thus, Adivasis are also referred to as Scheduled Tribes (STs). Some states with a sizeable population of Adivasis are Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Sikkim, Assam, Nagaland, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Tripura and Arunachal Pradesh. About 94% of the population of Lakshadweep consists of Adivasis.

The Adivasis are not a homogeneous lot. Each tribe has its own customs, language, social laws, traditional costumes, and so on. Many have distinctive dance forms, musical instruments and traditions of handicraft. Though only a few tribal languages, such as Santhali, have scripts, there is quite a lot of literature in the tribal languages. These languages are different from the mainstream Indian languages in that they are not derived from Sanskrit, the Dravidian group of languages or Persian-Arabic.

For all their differences, tribal communities have some things in common. From pre-British times, they have inhabited hilly, forested areas and depended on hunting, fishing and gathering forest products. The cultivators among them mostly practised (many still do) shifting cultivation, in which a forest area is cleared, cultivated for a few years and then left to be regenerated by natural processes. The settled cultivators used traditional methods of farming, but never lost their connection with forests. Thus, the tribal communities have a deep knowledge of forests, which includes valuable information on medicinal plants, natural pesticides, dyes and resins. Their religions teach them to worship spirits residing in trees, animals, groves, water bodies, hills, and so on.

Tribal societies are also 'more equal' than the mainstream Indian society. There are no distinctions along caste lines and there is not much difference between the social status of the members.

Interaction with other communities

Though the tribal communities have retained their distinct identities, it is not that there have been no exchanges between them and the other communities. Christianity, for example, has had a great influence on tribals and a lot of tribals have become Christians. There has been a lot of give and take between tribal and Hindu traditions, too. The deities (gods) Jagannath and Kali are probably of tribal origin. The worship of certain animals like snakes may also have been borrowed from tribes.

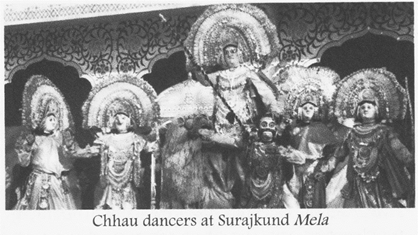

On the other hand, Chhau, the martial dance of tribal origin, popular in Odisha, Jharkhand and West Bengal/ shows clear Hindu influence. The dancers wear masks depicting Hindu gods and goddesses and enact stories from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas.

Before the British period, tribal communities had control over large areas of land. They had trade links with the neighbouring kingdoms, to which they supplied forest products, such as bamboo, timber, wax and honey. Sometimes they got involved in power struggles. Tales are told in Rajasthan, for example, of how a king of Chittor was helped to regain his kingdom by a Bhil Chief. Later, Maratha Chiefs paid a kind of tax to Bhil Chiefs to protect their lands from Bhil raids.

Loss of status

The tribal communities slowly started losing their status under British rule. Some of their forests were made reserved forests and sanctuaries. Some were converted into plantations, and others taken away for mining and industries. Large areas were flooded due to the construction of dams and great areas of forests were taken over to extract timber on an industrial scale. The people, who thus lost not only their homes and their means of livelihood, but their way of life and their cultural roots, were hardly paid anything in return. Thus, they were forced to work on plantations, construction sites and as domestic help, for very low wages. Large numbers migrated to other countries and many died, unable to cope with the change in their lives. Tribal lands continued to be taken over for mining, industries, dams and wildlife sanctuaries even after Independence, and the process is going on even today. The tribal people are cheated of their land and property, forced to work as labourers and agricultural workers, looked down upon for their customs and considered primitive.

Protests and armed struggles

The most famous tribal revolt against the British was the Munda revolt, led by Birsa Munda. Other tribes that revolted were the Santhals (in the east), the Bhils (of central India), and the Khasis and Garos (of the Northeast).

Through the 1970s and 1980s, the Adivasis launched large-scale protests demanding equality, land rights and an end to ill treatment at the hands of powerful groups. In the 1990s, C. K. Janu, an Adivasi activist from Kerala, started a movement to demand land for landless Adivasis. She formed the Dalit-Adivasi Action Council and was awarded by the state government in 1994. However, she returned the award to protest against the government's 'lack of response'. She pointed out that the various state governments are to blame for the violation of the rights of the Adivasis since they allow industries to come up on Adivasi land and evict (drive out) Adivasis to set up sanctuaries and build dams.

The tribal struggle in the North-east has become rather complicated, with inter-tribal rivalries and armed groups threatening the security of the country. The government has posted large numbers of armed forces personnel to deal with the situation. The constant warfare has only worsened the lot of the tribal people.

THE SCHEDULED CASTES

The Constitution lists certain castes that are to be given special privileges because they have been treated unfairly for centuries. Members of these castes, referred to as the Scheduled Castes (SC), had the lowest status even among the Shudras. They did jobs that were considered 'unclean', such as working with leather, cremating dead bodies and cleaning human excreta. Consequently, they themselves were looked upon as 'impure or unclean' by the other castes. They lived outside the main village or town, were not allowed to enter schools or temples, could not draw water from the village wells, and so on. They were untouchables. If a member of an upper caste accidentally came into physical contact with an untouchable, he or she would use ganga jal to purify himself or herself. Mahatma Gandhi, who worked hard for the equality of the untouchables, coined the term Harijan for these castes. Now the term Dalit (meaning crushed) is often used for them. You have read about social movements in their favour in Chapter 1 of the history section.

Manual Scavengers

These are people who remove human excreta from dry latrines (which cannot be cleaned by flushing), using brooms and tin plates, and carry it in baskets and tins to disposal grounds.

Q. Do you know why Dr. Ambedkar converted to Buddhism towards the end of his life? What do you feel about this?

They are mostly Dalit women and girls, who work in sub-human conditions and often suffer from diseases of the skin, eyes, and the respiratory and gastro-intestinal systems. Sweepers, who sweep roads and dispose of domestic waste in towns and cities, also work under unhygienic conditions and mostly belong to Dalit groups.

Know a Little More

Sulabh International is an organisation launched by Dr Bindeshwar Pathak in 1970. It has set up a large number of pour-flush public toilets (sulabh shauchalaya) which are used by about 10 million people every day. The organisation works to free scavengers from their unhygienic jobs. It also helps to train poor boys and girls, especially scavengers, so that they can find other jobs.

TRIBAL PROTESTS

? The Nyamgiri Hills in Odisha are considered sacred by the Dongriya Kondh tribe. The government had given clearance to an international mining company to set up a mine and refinery in the area. The tribals launched a very successful protest, which was joined by environmentalists and international organisations. The outcome of the protest was that the environment ministry cancelled clearance for the project and the company took the case to the Supreme Court.

? In January 2006, tribals gathered to protest against the unfair acquisition of land for a steel plant in Kalinga Nagar in Odisha. The police fired on the protesters, killing 12 Adivasis. A state-wide bandh was then called against the cruelty of the state government. Protesters also carried out a road block for 14 months. Later, the high court intervened and the state government agreed to the demands of the people.

Protests

Like the Adivasis, the Dalits too organized themselves to protest against ill-treatment. During these protests, they suffered backlashes in the form of violence, humiliation and social boycott from powerful groups. However, the protests led to the formulation of laws and the announcement of measures for their protection. In some cases, as in the case of C. K. Janu's Dalit-Adivasi Action Council, Dalits have joined hands with Adivasis

PROMOTING SOCIAL JUSTICE

The Preamble of the Constitution promises to secure social, economic and political justice for all citizens. Every citizen is entitled to the Fundamental Rights of equality and freedom, the right against exploitation and the right to constitutional remedies. Article 17 of the Constitution forbids the practice of untouchability, while Article 15 forbids discrimination on the basis of religion, race, caste, sex, etc. Thus, the Constitution has ample provisions for the weaker sections of society. Yet new laws have to be framed from time to time because it is not easy for these sections to secure their rights.

PROTECTION OF CIVIL RIGHTS ACT

This Act makes the practice of untouchability punishable by law. Anyone discriminating against members of the SCs can be punished with imprisonment and fine.

SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES ACT

The full name of this Act, passed in response to Adivasi and Dalit protests through the 1970s and 1980s, is the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act (1989). Some actions that are punishable under this Act are:

? Hurting or humiliating members of the SCs and STs by forcing them to eat or drink anv inedible substance, unclothing them, parading them naked, etc.

? Taking away the land or property of members of the SCs/STs and forcing them to perform slave labour (work without wages)

? Assaulting or dishonouring women belonging to the SCs/STs Special courts have been set up to try cases under this Act.

LAW AGAINST MANUAL SCAVENGING

The Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act was passed in 1993 to stop the inhuman practice of manual scavenging. However, the practice continues, as the Safai Karamchari case will tell you.

FOREST RIGHTS ACT

The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act was passed in 2006 in response to Adivasi protests over being evicted from their traditional lands. It recognises the right of forest dwellers to live in forest land, and use and sell forest products. It also allows them to fish in water bodies and graze their animals on forest land.

JUSTICE AND THE MARGINALISED

Five upper caste persons in Kerala were accused of violating the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Four witnesses gave evidence in court that the accused had threatened some Dalits with a gun to stop them from using a well. The trial court convicted all five accused. The sessions court acquitted two of them, while the high court acquitted all five, rejecting the evidence of the four Dalit witnesses as unreliable. Finally, the Supreme Court gave a decision in favour of the Dalits.

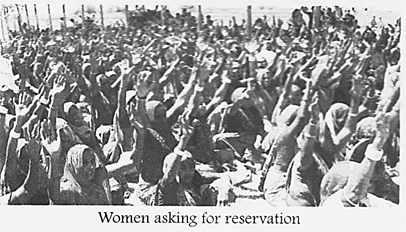

RESERVATION POLICY

The Constitution directs the government to make special provisions for the weaker sections to bring them at par with the rest of the country. Accordingly, the government reserves 15% of seats in educational institutions for the SCs and 7.5% for the STs. Similarly, jobs in government offices are reserved for these sections. The reservation of seats does not mean that anyone from these communities can qualify for these seats or j obs. It means that members of other communities cannot compete for these seats or jobs. Also, in most cases, the qualifications (or marks) required for members of SCs and STs are lower than those required for members of the other communities. The government also helps students from 'backward' communities by setting up hostels, providing scholarships and arranging coaching classes. According to the advice of the Mandal Commission, set up in 1979, the government reserves an additional 27% (over and above those reserved for SCs and STs) of government jobs and seats in institutions for higher studies for the other backward classes (OBCs).

RELIGIOUS MINORITIES

The Constitution forbids discrimination on the basis of religion and allows every religious community to practise its religion in the way it chooses. Minorities also have some special rights related to culture, education and personal laws. Yet minorities do face discrimination. In the case of Muslims, especially, various factors, including discrimination, have led to marginalisation. In 2004, the government set up a committee under Justice Rajinder Sachar to find out about the status of Muslims. The Sachar Committee report, presented in Parliament in 2005, has raised several controversies. However, it is worth looking at some points raised in this report and by some other studies.

? The status of Muslims is above that of the SCs/STs/ but below that of the OBCs.

? In comparison with children of other religious communities, Muslim children in the age group of 7-16 receive fewer years of education. The literacy rate among Muslims is also lower than the national average.

? On an average, areas inhabited mostly by Muslims are less developed and have fewer public facilities, such as electric supply, piped water and good roads.

? Though Muslims account for about 13.5% of the population, they constitute only 3% of the administrative services (IAS), about 4% of the IPS, and so on.

The Sachar Committee recommended reservation for Muslims with traditional occupations that are similar to those of the SCs. Though this has not come about yet, a National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities has been set up. The commission is responsible for identifying the socially and economically backward sections among minorities and suggesting steps for their welfare.

LAWS AND REALITY

Six years after the law against manual scavenging was passed, the Safai Karamchari Andolan, an organisation fighting for the rights of manual scavengers and sweepers, along with six other organisations and seven manual scavengers, filed a PIL in the Supreme Court for the enforcement of the law. They presented evidence to show that the number of manual scavengers had increased after the passing of the law and that government organisations, such as the Railways, were continuing to employ manual scavengers. The Supreme Court directed the government to prepare a time-bound plan to put an end to the practice. However, the practice still continues.

Visit the Safai Karamchari website to find out more about this issue.

You need to login to perform this action.

You will be redirected in

3 sec